Being John Travolta in Tehran

Note: On Friday July 5th, there will be a second round of presidential elections in Iran. This post is not about that because I needed a respite from this summer of hair-pulling elections: Iran, UK, France, US.

Despite the best efforts by various groups to present the elections in Iran as meaningless and predictable, reality tells us that they are neither. There are two very different candidates running and much of the unpredictability lies in whether and how the turnout will increase in the second round. To avoid collapsing wishful thinking or political agendas into reality, the analysis of the elections must, alas, wait for the elections to actually occur. At the end of this piece however, I’ve included some articles/references that can give insight into what is going on right now. More to come later.

Nothing was going to make me look like him but thankfully only I knew what he looked like, I thought, as I stood on tiptoes to take a serious look at my face in the mirror above the sink: chin up, lips pursed, hair tightly clamped down to my skull with a million bobby pins. I momentarily thought about running into my grandmother’s kitchen to spread some ghee on my hair to give it that sleek look but decided against it. So instead, I carefully tucked in my pink button-down shirt and then held my breath and pulled in my stomach to zip up my tight brown corduroys.

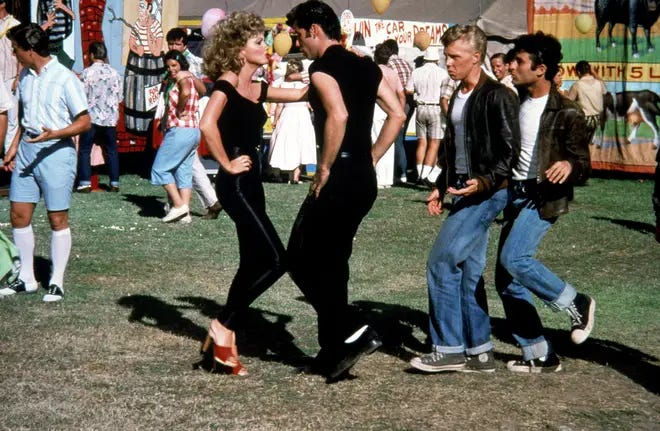

I strutted out of the bathroom, one foot gently bouncing in front of the other as I had seen him do, and leaned against the doorway staring at my friend—correction, my only friend—Mina who was standing in the middle of the room in her frumpy blue dress and her black hair straight down to her chin. She looked all wrong too, I thought. But there was no time to dye her hair blond (not that she would have even let me) or curl it or find large gold hoop earrings. Plus, she’d never even heard of leather pants, let alone own one. This would have to do, I thought with a sigh. It was the summer of 1981, I was Danny, she was Sandy, and Grease was the word in my grandmother’s neighborhood in Tehran or so help me god!

Mina was just three months younger than me and a walking jukebox of old Persian songs that lifted her away from an existence as the middle child in her family. Neither the first-born son, nor the pretty daughter, nor the youngest boy, Mina existed as an afterthought to her family. So when I popped up in my grandmother’s neighborhood, a clueless nine year old who had spent most of my life in California, she greeted me with unfettered joy. Navigating this fresh-off-the boat Americanized kid through the intricacies of my grandmother’s traditional neighborhood and the delicate dos and don’ts of an Iranian girlhood gave Mina the status she craved to have. At least this is how I understand why it was that when in a bout of boredom on a hot summer day I told her the plot of Grease and then suggested that we recreate the dance scene at the end (“It’s basically when he asks her to marry him and she says yes”) and perform for the neighborhood women, she agreed on condition that she be the girl. “It’s not proper,” she said in her faux adult way, “for a girl to be a boy.”

“Come on!” I said to her leaning off the doorway a little annoyed. “We need to practice one more time!” I walked across my grandmother’s room and pressed play on the tape recorder. Dum…dum…dum, went the familiar beat as I did the best imitation of a teenage leather-clad boy from the 1950s a 9-year-old girl strutting on a carpet could muster. Mina just stood there looking perplexed.

I got chiiiiiiiiills, they’re multiplying, and I’m looooooosing con-tro-hoooool, I mouthed as I took off my imaginary leather jacket. And then when it got to it’s electrifyin’, I made jazz hands and fell down on the floor, my face grazing Mina’s feet. “Uh…where’re your shoes?!” I said from down below, my cheek still on the coarse wool carpet. “What do you mean?” she replied, not even bothering to bend down to see what was going on. “SHOES!!!!” I yelled, getting up and brushing off some lint clinging to my pink shirt. “I told you, you now have to act like you are throwing down your cigarette and then put it out with your heels!!!!”

“What shoes?” she shrugged, “you can’t wear shoes on the carpet,” taking on the patronizing tone she liked to use when explaining the subtleties of Iranian culture to me. “People eat on this carpet and your grandma praaays on it. You can’t EVER wear shoes. EVER!” She was right and I was wrong so the only thing I could do was to give her a chilly stare as I walked up to the cassette player and pressed rewind for 2 seconds, then play, then rewind, then play, then rewind, then…until I had cued the song to the beginning. Still annoyed, I pressed eject and stuck the tape into my back trouser pocket. This, I thought angrily, was just one more obstacle I would have to ignore to spread the gospel of Grease.

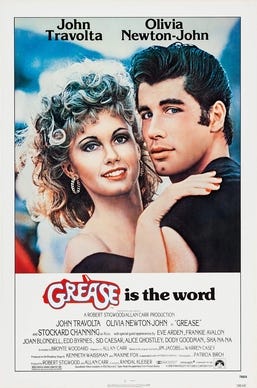

When Grease came out in 1978, I was 6 and living in San Diego. By the time I turned 8, watching Grease had become my obsession, my raison d’etre, my singular desire in the whole wide world. I still can’t figure out why. Was it the use of “bad words” that sparked this subversive love in me? Was it the glorious Olivia Newton John (even more glorious in Xanadu, which combined my love of her with my love of roller skates)? Or was it that from day one, my mother had been steadfast in her refusal to let me watch it? Every time I begged her to let me see it, she had done that thing Iranians do to let you know their mind is made up: She had slowly lifted her chin upwards, held it in the air for a second, and clucked “nooch” with her closed mouth. The “nooch” meant that doors of negotiation were closed. The “nooch” meant that nothing would change my mother’s mind. Nothing, that is, but a full-blown revolution.

From late 1978 and into 1979, I would sometimes watch television with my parents as a sea of people, fists raised in the air, shouting “death to the Shah” filled up our tiny living room. While the stern looking cleric with the salt and pepper beard was clearly the star of the show, I was drawn to the sophisticated looking women and men in bell-bottoms, side beards, and feathered hair that spoke with passion about justice and the end of monarchy. They looked like my parents and their friends. They looked like the Iranian students I had watched argue passionately from my perch on my dad’s shoulders when he had taken me to his university. They looked like my cousin, she of the long raven hair who had come from Iran to live with us and attend university but had suddenly gone back, leaving behind only her pink hairbrush, which I had coveted for months. “The king is unjust,” she had told me, “and the people are on the streets. I have to go back.”

So my cousin left and the revolution came, and nothing really changed for us in San Diego. Sure, the king and his coterie of bowing men in suits were replaced on our tv screens with angry bearded men and turbaned clerics. And sure, there were more tear-filled calls to Iran from our cream colored phone that hung in the kitchen as my parents’ longing for home increased along with the fear that the borders will close and forced them into exile. But still, my father would sit at the dining table by the kitchen and type up his dissertation, the click-clack of the typewriter blending with the sound of my brother’s banging on his high chair, and the hum of the television I liked to keep on while I did my homework. Still, when I came home from school, I would sit petulantly at the table with my mother and go through the textbooks she had ordered from Iran so that I would be literate in Persian. Still, on weekends I would race my bike through the leafy green of our apartment complex, eating candy that turned my tongue into the blue of antifreeze. And still, I would beg my mother to let me watch Grease.

Then one night as I lay in bed reading, I heard the familiar cords of “Summer Nights,” Sandy and Danny’s first duet and I knew, I just knew my mother was watching it on television. I jumped out of bed and ran into the living room. I’m only here, I said to my mother who was curled up on the couch, to get some water, as I walked slower than any human ever has towards the kitchen. I turned the faucet enough for a drip to get going, and held my water glass under it, relishing the song as it snuck into my ears. By the time the glass had filled up, the scene had ended and so I walked at a human pace towards my bedroom when my mother said: “Sit down. Let’s watch it together.” I should have known then that something was up; I should have realized that only a revolution could reverse my mother’s nooch. Instead I was so overwhelmed with joy that I ran up to her, nestled myself against her chest, and let the music take over me.

Several months later we were in the newly minted Islamic Republic of Iran.

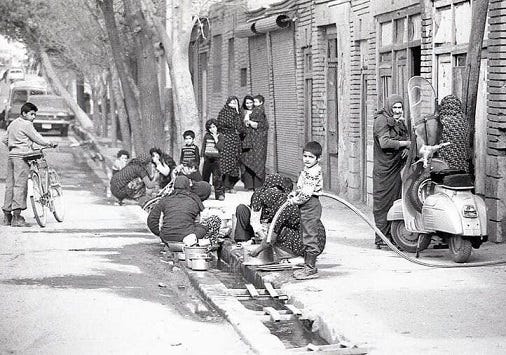

When we returned to Iran, we headed straight for Islami alley no. 6, which had been my grandmother’s house for as long as I remembered and which became home for the next 15 months. Islami alley was an alley like any other in south Tehran, where the weather was more polluted than the north, the people poorer, and the buildings older. A small joob, one of the many shallow canals that ran the length of the city, split it in two bringing with it a steady stream of water and wads of trash from uptown.

It was a long alley, so long in fact, that when I stood in front of my grandmother’s house and peered into the distance, I could not see one end. But it was also short for it contained an undrawn, imaginary line that I was not allowed to cross alone. Beyond that line, I was told by my elders, and pretend-elder, Mina, “nothing good ever happened.” Beyond that line, there were no street lamps to light up the alley at night, and somewhere there, way over there, Mina sternly told me, lived a family with a daughter not quite right in the head. “They never let her out,” she said in a whisper one day while we were standing in front of the house. “They’re not good folks, so if you go down there, you’re clearly up to no good yourself. People will talk and your family’s ab-e ru will be lost.”

The end of Islami alley closest to my grandmother’s led to a narrow one way street where if one turned left, it would eventually lead to the mosque where a decade later we would mourn my grandmother’s passing. But back then, there was no need to take a left. Right, always right, is the way I walked no matter where I was going, although usually, I was just going to Mina’s house.

Sternly and continuously, my grandmother would instruct me as I would put on my shoes: Don't look up, don't talk to anyone, just go out, right, left, left, and into their house. And so I would: past the boys idling on the corner, dying to give cat calls but too scared of my grandmother’s wrath; past Qasem aqa’s tiny white store from where we bought chocolate milk in bottles, KitKats, and pofak cheese puffs that Mina swore were made of kerosene (“Light a match and see if I’m wrong,” she’d constantly dare.); past the “cotton beater,” who could be seen everyday through his wide open doors crouched inside a cloud of cotton, whipping it into perfection as he fixed the neighborhood’s mattresses; past the wondrous Vespa repair shop with its intoxicating smells of motorcycle oil and gasoline. Then, I would take a left and immediately inhale the smell of fresh taaftoon bread pouring out of the always packed bakery, and keep walking towards the halal mortadella and sausage shop across the street from Mina’s alley. Another left and into the heavy metal door that was always open.

I must have walked this route at least 10 times a day that first summer in Iran, always finding an excuse to go back and forth between the houses; always finding an excuse to breathe in the smells and occasionally run my hands along the jagged brick walls of the houses and shops. Behind those bricks, I knew, women gathered in the open-air courtyards to hand-wash clothes in plastic tubs, spread a cotton sheet on the floor to sit together and clean kilos and kilos of herbs and vegetables, or huddle on makeshift mattresses of thick blankets during siesta time and whisper in excited tones. This made my grandmother’s alley and her entire neighborhood seem like a bottom-less well of secrets and rumors to be discovered. And if I had to drag my reluctant cousin to every single house and dance to “You’re the One that I Want,” just so I could find out whose husband was rumored to be sleeping with boys, which neighbor was a divorcee, whose son was using drugs, and what really was up with the girl on the forbidden end of the alley then by golly, I would.

And so here we were. “We go?” I said to Mina, still standing where I had left her, staring into my grandmother’s courtyard, and humming one of the songs from the jukebox in her head. “We go,” she said, a bit more gamely than before. By the door of the living room lay a cornucopia of shoes. We bent down and searched for our identical white plastic slingback sandals that were all the rage then and put them on. Shoes on feet, tape in pocket, we left the house, took a few steps to the right, and pushed open the door to no. 4, Ateqeh khanum’s house, where we promptly took off our fashionable plastic sandals and added them to the pile of shoes.

As we entered the cool covered entryway, we could hear the hum of gossip seeping out of the living room. I was so nervous I thought of going back. But faith, even, or particularly, when it concerns the Grease soundtrack is a powerful thing. The room looked much like my grandmother’s furnished with a raised wooden platform that served as a bed or a couch, depending on the time of day. Several overlapping wool carpets covered the stone floors. The women of my grandmother’s neighborhood were seated on the edges of the room, each one wrapped in floral cotton chadors, the informal veil one wore to the corner market or the neighbor’s house. Most of the chadors had gently slipped off their heads and was just sitting on their shoulders. Mina was already one step ahead of me, fully activated as the adult she dreamed she was: Salam, may I sacrifice myself for you, are you well, please please, don’t get up, yes my mother is well, she sends her regards, may I sacrifice myself for you, you’re too kind. Yes, yes, just arrived from America.

The obligatory exchange of pleasantries so crucial to Iranians from all walks of life was dizzying so I nodded and half-heartedly pledged to sacrifice myself too as I declared the well being of my entire family, including my two-year-old brother whose regards I sent to everyone who asked about him.

We sat there cross-legged on the floor for a while as I shifted my weight from one leg to the next, wondering why in the world I thought this would be a good idea. Then suddenly it all happened: A cassette player held together by duct tape appeared and I put the tape in, instructing Ateqeh Khanoom’s daughter to press play on my signal. As Mina and I took our places in the middle of the room, the hum of the women’s chatter was replaced by little hushes here and there, and the odd giggle. Then I gave the signal, and the music that I loved, the music that held memories of biking through leafy green streets and tongues blue with Fun dip candy and the scent of my mother as we watched Grease in our small living room in San Diego filled up the room. I removed my imaginary leather jacket, Mina put out her imaginary cigarette with her imaginary stiletto, and as Sandy and Danny ecstatically crooned “you’re the one that I want,” we held hands and skipped barefoot as gracefully as we could across the carpet.

If you’re here for information on Iran’s upcoming second round of elections on July 5, 2024:

To get a no nonsense overview of the candidates, the discussions, and the turnout read this from Amwaj.

I follow a lot of people on Twitter (X, whatever), some of whom are doing good real time analysis and others who are just saying water is wet (i.e. neither saying anything interesting or accurately since water makes things wet.) There are too many to mention but take a look at Alireza Talakoubnejad who’s been doing a great job following the elections carefully and translating some of what’s only in Persian it into English.

Azadeh Moaveni has a lovely piece in the London Review of Books from her recent trip to Tehran on the eve of the first round of the elections. It’s less about the politics of who’s who and whether to vote or not, and more about all the little things that make a place a place. Its observations include bookstores, the international food expo, and billboards around town. It ends with this sentence: “There is very little graffiti in Tehran anymore, but last week I saw scrawled on a wall in the city centre: ‘Alone, tired, numb, sad.’”

If you read Persian, Factnameh is fact-checking the candidates’ claims and campaigns.

If you haven’t already read it, don’t miss this piece I translated and published last week from someone inside Iran laying out her thoughts and struggles with the question of voting in the aftermath of the Women, Life, Freedom movement.

And these are the true things for this week!