One Was, One Wasn't یکی بود یکی نبود

The classic (and somewhat befuddling) start to fairytales in Persian

For years now, I’ve been thinking about something I called the Laura Book. I named this unwritten book after Laura Gross, my agent and patient friend (or is it the other way around?) because she’s been asking me about it for over a decade. This past month I began writing it more seriously than I ever had before. (Thank you Jackie heart heart and smiley face.) If (sorry, when) I finish it, I’m going to call it …what else but my mom’s perfect sentence? For these are indeed the true things.

Right before first period started, I slipped into the desk next to the classroom door. I sat upright hoping no one had seen me, heard me, knew I was there. It was my first day ever at a Los Angeles County high school in the US of America and I was dressed in what I had been told was the latest fashion of 1989: a white short tennis skirt, horizontal pink and white shirt with a small white pocket sewn on the left chest, hot pink knee-high socks scrunched down to my ankles, and white tennis shoes. If anyone had bothered to look at me, which up until then they hadn’t, they would have seen that my shirt and skirt were handmade by my mother who put her home-economics skills into excellent use by helping her teenage daughter feel a little less out of place. But I still felt awkward with my dark brown hair that was neither long nor short, neither curly nor straight, neither frizzy nor smooth. The 40 or so kids in my first ever American high school class all seemed to be happily chatting away with their friends with nary a glance in my direction. That suited me fine.

I slumped into the chair and let myself relax for a second, taking in the room. It was a high school classroom like all the others I’d seen in the movies: a blackboard to my right, the teacher’s desk to my left, rows of individual desks and chairs populated by all sorts of kids. I even spotted some Iranian ones. The room looked old and tired and had an unfamiliar smell. Chemicals maybe? There was a banner that ran atop the blackboard that read “What We Have Here is Failure to Communicate.” I could not figure out why the English teacher was advertising his failure. But then again, I did not understand America. Failure to understand is what we had here, I thought to myself.

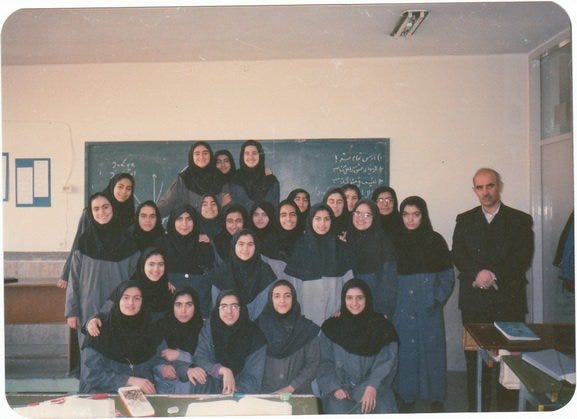

Just weeks ago, I had been sitting in another classroom—in MY classroom in MY city of Tehran, surrounded by girls I had known since I was 11. We all dressed in our school’s uniform of grey manteaus and black or navy maqnaehs, some made by our mothers, others by seamstresses, others bought off the rack. Instead of advertising failures to communicate, school murals focused on those of imperialism, of America, the Soviet Union, England, France. Fine! The world! The Islamic Republic of Iran was all around us. Most of us didn’t like it but we understood it and because we understood it, we could ignore it. But this place? It was so alien it required your constant attention. First period had barely started and I was already exhausted.

I was staring slack jawed at some girl sitting on a boy’s lap (right in front of the teacher?!!) when I felt a sharp pain burn through my right arm. I opened my mouth to scream when I saw a thumbtack where the pain was sharpest. Someone passing by the classroom had pressed it into the nearest arm they could find—mine. (The school nurse later on assured me it was a prank. I went home and looked up the word in my dictionary. What the hell?!) I closed my mouth. Screaming on the first minute of the first period of the first day of school when you’re wearing handmade clothes was not how I wanted things to start. But the pain was searing through my arm. Just a month earlier, Mrs. Borqeh-i, my school’s history teacher slash revolutionary mumbo jumbo bullhorn upon hearing that my family was immigrating to America had vomited a rant on the school’s staircase about how the West was stealing our country’s greatest minds (Yes. Me!) They weren’t stealing us, I thought, as the pain radiated out of my upper arm into my neck, they’re trying to kill us!

I kept blinking hoping to stop the tears that desperately wanted to come out of my eyes to no avail. I was now the weirdo who kept blinking and tearing in the last row. I looked around and thankfully I was still invisible. So I peeled myself off the wooden chair really slowly and scoped the route that involved the least number of eyeballs to the teacher’s desk. The bell rang.

“Excuse me,” I whispered. Dr. Harrison looked up. “You’re the new student,” he said slowly, unsure if the daze in my eyes was language related. “We’re going to start class now. Just pick any open seat and I’ll bring the textbook to you.” I nodded. But didn't move. “Excuse me,” I said again, then turned a little to my left to show him the thumbtack. I prayed he wouldn’t overreact. Little did I know that Dr. Harrison had been teaching high school for several decades and could not be fazed. He just looked sad and, I imagined to myself, a little embarrassed for being a teacher in such a barbaric place. He walked me through the hum of teenagers talking and laughing and told me where the nurse’s office was. “Get it cleaned and come back,” he said and handed me a piece of paper that he told me gave me permission to walk the halls. I started to walk away but decided to look back, wave with my non-mutilated arm, and smile.

We had come to America barely two weeks earlier, on Christmas eve, through Rome. The “we” here was my mom, my four year old sister and I. My dad and my 9 year old brother had traveled to Los Angeles earlier when the war had still been raging. During those 6 months when our family had been split in two, a ceasefire had ended the eight-year war with Iraq, we had finally been given a home telephone line after waiting for our turn for 7 years, and I’d fallen in love (my best friend thought I was just bored)—in ascending order of importance. I have no memory of our reunion, or what it felt like to hug my little brother, or to get to literally look up to my dad again as I had done all my life. I do remember though that when we landed in Rome, our flight to LA had been pushed to the next day so my mom, sister, and I strolled down the twinkly streets and I felt something like free and something like fear. But above all else, I felt strange in all senses of the word.

Overnight we went from living in a large 3 bedroom apartment in polluted, crowded, alive, bustling and familiar Tehran to a tiny 2 bedroom in sleepy Tarzana, CA where to be a pedestrian, let alone take the bus, as I had to every day, was akin to announcing to the world that you were poor. The fact that I was fluent in English just made everything worse. I could speak the words, I could comprehend the sentences, but the meaning behind everything people said, particularly people my own age, eluded me. It felt like the minute we stepped off the plane, I could only hear but see nothing.

By the time I found the nurse’s office, I literally couldn’t see anything, blinded as I was by tears. I felt sorry for myself. I felt shame as if this wasn’t a random act of violence—a prank—but one targeted at me, at the weird Iranian kid roaming the halls of Taft High School. A day later, I realized the school was full of Iranians, some fresh off the boat like me and some born and raised in Great Satan land, but I still could not shake the feeling that the thumbtack attack had meaning specific to me. That the universe, if not the other kids, were trying to tell me something. And that something was to go home. Home home. Not here home. Go back to Iran where I belong. But I couldn’t. I was officially an immigrant now.

***

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about how in America we celebrate immigration and we vilify it when all it is, is just hard. At the end of the day, no one really wants to leave home while also falling into a lifelong yearning for it. But we immigrate because at some point we want a different life (imagined always as a better life) and slowly that want turns into a burning desire that fuels one of the hardest things you can ever do. Even though my story of immigration barely registers as a story of hardship in our world today (the cruelty towards refugees and immigrants makes many things feel like a walk in the park), the older I get the stranger it seems to me.

How strange, for example, that I had nothing in the United States of America that dated to before December 24, 1988, beyond my parents and my two siblings. Back in the early 1990s, I had a Lebanese boyfriend who had come to MIT by himself. No parents, no siblings. We met on the first day at orientation. After a couple of years of…let’s call it interrupted dating, he would comment on how our relationship was the oldest thing he had in America. That stuck with me. For the longest time, I could not stop thinking about how I only knew 4 people from before 1988. It probably explains why every relationship felt intense and every good-bye a heart stabbing act of abandonment.

Being an immigrant is about hope but not in the way Emma Lazarus wished it to be. Sure, it’s about a “yearning to breathe free.” But it’s also about the hope that you can pull out your roots and grow them again in soil that is sometimes hostile and always different. It’s about not thinking of the pieces of you that, I wouldn’t say are left behind, as much as thrown into a black hole and sucked out of existence.

What does it mean to be an immigrant? It means to accept that there might be no continuity between where you die, where you live, and where you were born.