The Gadfly

A Personal and Revolutionary History

For a while now I’ve been wondering why was it that I, the girl known to never leave home without at least 3 or 4 books in my bag, only brought two books with me when we immigrated to the US in 1988? One of them was a book given to me by a doe-eyed boy who loved me but whom I did not love back. The other was The Gadfly [Kharmagas] by the Ireland-born Ethel Lillian Voynich.

Published in the US in 1897, The Gadfly is a melodrama set in Italy during the 1830s rebellions against the Austrian empire and the Italian movement for unification. A young Englishman, Arthur Burton, travels to Italy to become a priest only to join the Young Italy movement, smuggling and distributing illegal revolutionary pamphlets. When a priest passes information to the police that Arthur had revealed in his confessions, his comrades, including the committed revolutionary Gemma, his childhood friend and crush, believe he has betrayed them. At the same time, he finds out the man he considered his mentor into priesthood, Father Montanelli was actually his biological father who had broken his vows in a night of passion with his mother. It was all too much so he does what any young man would do: Fake his own death, travel to South America, endure many hardships, and return to Italy as a revolutionary anti-clerical journalist who publishes radical tracts under the pseudonym “the Gadfly.”

Eventually, the Gadfly is arrested and condemned to death. The priest who comes to give him his last rites is none other than Father Montanelli who only then realizes that the Gadfly is his son, Arthur. In their final conversation the Gadfly/Arthur asks his Father/padre to choose him over his faith. “How much do you love me? Enough to give up your God for me? What has He done for you, this everlasting Jesus,—what has he suffered for you, that you should love him more than me?… I demand nothing. Who shall compel love? You are free to choose between us two the one who is most dear to you. If you love Him best, choose Him.” Heartbroken, Montanelli leaves the prison and the Gadfly is executed by a reluctant firing squad. Montanelli then goes mad with grief and dies of an aneurysm. (The last words of the novel deliciously are: “Aneurism is as good a word as any other.”) Finally, in the epilogue, Gemma finds out the Gadfly’s true identity and Arthur’s love for her in the most excruciating way: A letter that arrives for her after his death. “The writing grew suddenly blurred and misty. And she had lost him again—had lost him again! At the sight of the familiar childish nickname all the hopelessness of her bereavement came over her afresh, and she put out her hands in blind desperation, as though the weight of the earth-clods that lay above him were pressing on her heart.” As Gemma cried reading Arthur’s letter, so would I, my heart breaking for a love that remained unrequited.

Since I first read this book in 1985 whenever I wanted to feel—like really really feel— the world, I would pick it up, flip to the end, read, and bawl. No wonder the yellowing pages of my copy are cockled. And no wonder it came across oceans with me. The Gadfly was the epitome of the life I wanted to live, a life suspended in the taut intensity of wanting and not having. For me, a kid in post-revolutionary Iran, The Gadfly was the ultimate love story. Somehow that it graced the shelves of everyone I knew, everyone who had either taken part in or observed the 1979 revolution, did not seem to raise in my mind the possibility that it could have also been a book about revolution.

Years later in a coffeeshop in London, a middle aged woman whom I was interviewing for my book on Iran’s revolutionary generation mentioned The Gadfly, along with The Soul Enchanted by Roland Rolland and Quiet Flows the Don by Mikhael Sholokhov as books that were responsible for her political awakening in 1970s Iran. I had not thought of the book, let alone read it, in decades. But wait, I thought, how come she mentioned it in the context of her politicization?

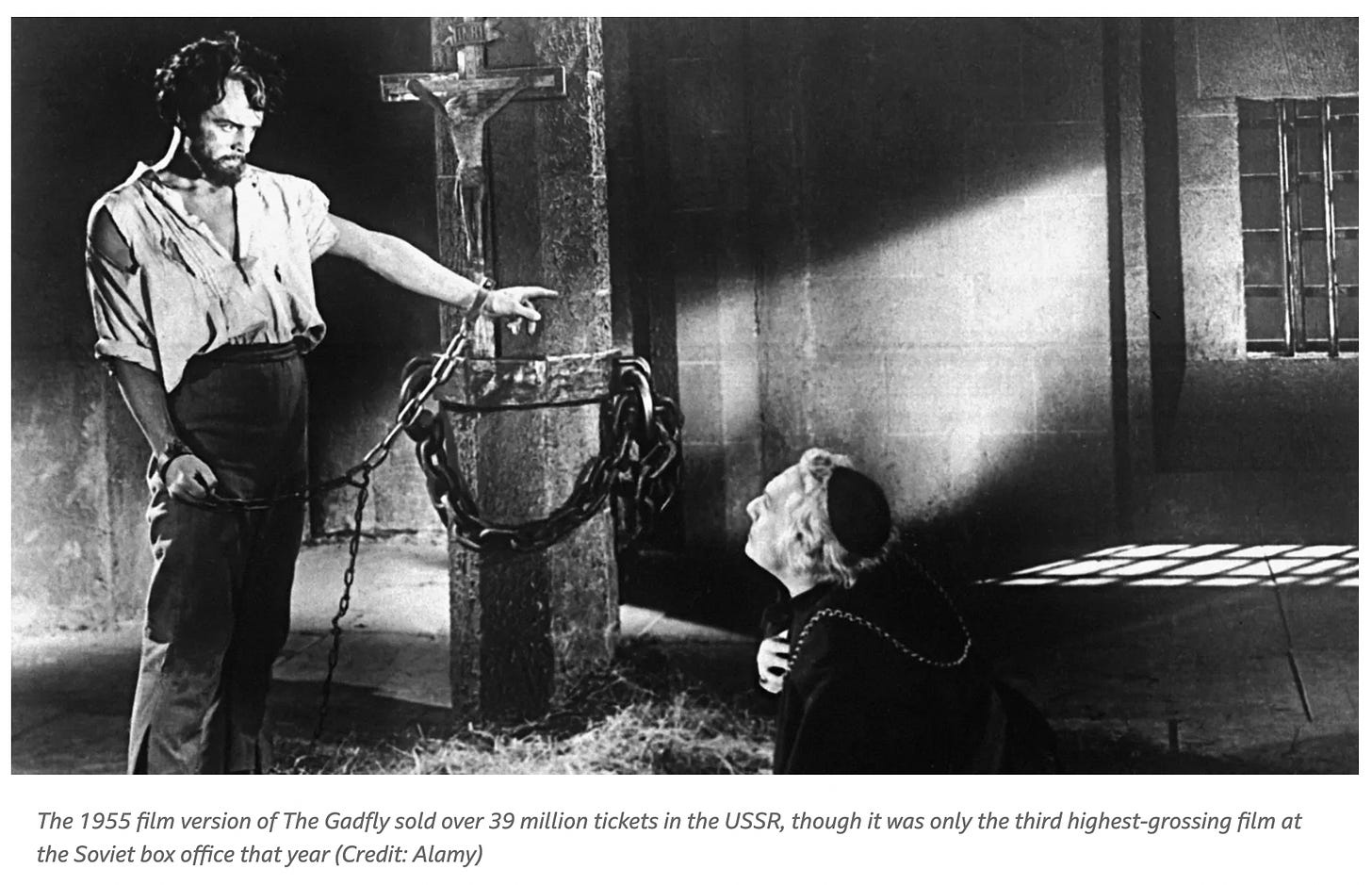

The Gadfly, it turns out, was not just a tearjerker melodrama but a cornerstone of the revolutionary canon for generations of people flirting with, if not outright taking part, in leftist political activism. In Iran there are 3 different translations of the book with the first translation, by Khosrow Homayounpour and published in 1962, currently in its 32nd reprint. Its popularity in Iran was only rivaled by its popularity in the Soviet Union where it sold anywhere between 2.5-4 million copies. There are many theatrical, musical, and balletic versions of it in Russian, Albanian, and Chinese, the first of which was written by George Bernard Shaw one year after the book’s publication. Shostakovich scored one of its many film adaptations. Its popularity elsewhere is made all the stranger by the fact that The Gadfly is virtually unknown and unread in the United States where the book was first published. (Read more about its global reach, including in Russia today here.)

When the book appeared in Persian, it raised no issues for the censors even though there are indications that politically minded readers had already seen in the book reflections of their own struggles. In 1963, The Gadfly was mentioned in a SAVAK report that covered a secret meeting in Tehran among members of the communist party, Tudeh. The report is a detailed breakdown of the meeting that included what one would expect of a 3 hour underground political meeting: An exchange of news, a 15 minute per member hearing of “suggestions,” and close readings of “party books” [ketab-e hezbi], which included tracts such as “Class Struggle” by Noureddin Kianouri, along with The Gadfly and Nikolai Ostrovsky's How the Steel was Tempered, a book whose main character explicitly credits Ethel Lillian Voynich’s revolutionary her for his own political bravery.

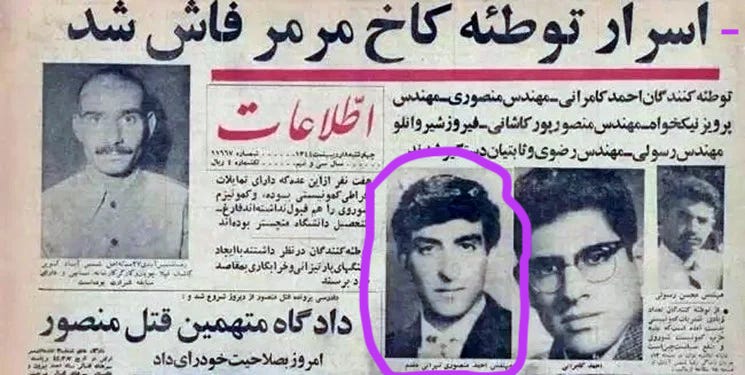

Despite its appearance in an illegal political meeting, The Gadfly was still deemed a harmless book 3 years after its Persian publication. In 1965 a member of the Imperial Guard tried to assassinate the king, Mohammad Reza Shah, while he was about to enter his office in Marmar Palace. The would-be assassin and two others were killed in the exchange of gunfire and two others, including a gardener were injured. Several men were arrested, some of them members of a Marxist group, and put on trial for masterminding the assassination. One of them, Ahmad Mansouri, was accused by the prosecution of giving subversive books to the others. But Mansouri’s lawyer was quick to point out that the books he had given them were “ordinary books like the Gadfly.”

Over the course of the next decade though, the book was treated as anything but ordinary, an evolution that was made possible by the monarchy’s increased sensitivity to books (of all kinds) and its expansion of censorship. A harmful book, as one censor explained to a young man before his arrest, was like drugs in a pharmacy. It might be legal for the pharmacy to carry it but not everyone should have the right to buy whatever drugs they want because it might be poison to them. And so by making some books legal one day and illegal the next or legal in the hands of some and illegal for others, the monarchy ended up expanding the meaning of what it meant to be political while simultaneously attaching a heavy price to it: By 1970, the sentence for having copies of books deemed harmful became 2 years in prison, a punishment that turned many politically aware but not active youth into full on revolutionaries.

Secret security documents reveal multiple instances where the possession of The Gadfly triggered an investigation into someone or was confiscated by the state. In 1972, the warden in a provincial town where many political prisoners from other parts of the country had been sent, reported coming across an anonymous cache of 8 pamphlets that covered a number of securitized topics. A translation of a biography of Ethel Lillian Voynich was one of them. In fact The Gadfly was so well known among political prisoners at the time that a former activist remembers how in 1975 in Iran’s notorious Evin prison, there was a 90 year old farmer named Yavar who whenever asked what he was doing there among all these young activists would say in his local dialect: I read the Gadfly, I became a socialist.

The prison humor seems not to have been very off the mark. The Gadfly was included in leftist reading groups and handed out by left-leaning teachers in schools to recruit students over to their revolutionary cause. In fact, that had happened to my interviewee in London who surreptitiously had been given the book by her leftist teacher.

There is so much to say about The Gadfly, particularly about its most fabulous creator: from the fact that Ethel had been born Boole, as in George Boole, the inventor of Boolean algebra, to her political activism before and after the Russian revolution, to the reasons for why she is all but forgotten in the US, to the persistent though most likely false speculations that the figure of the Gadfly was based on Sidney Reilly aka the Ace of Spies, an adventurer in the employ of the British Secret Services and one of the inspirations for Bond, James Bond. Some believe the two had an affair and Ethel took details of his early life—the illegitimate boy who goes to South America and returns a man—and gave them to Arthur Burton. Or, as more solid evidence shows, Reilly took the details from the Gadfly and made them his own. (Read more about Ethel Lillian Voynich here. There is no biography of her in English as far as I can tell.)

But I want to end on heartbreak again, though this time not my own, nor Gemma’s. I want to end on the surprising ways in which The Gadfly intersects with the life and the death of Bijan Jazani, revolutionary Iran’s foremost theoretician of armed struggle and whose name needs no introduction for most Iranians of the revolutionary generation, regardless of their political background.

On November 6, 1972 around 3 pm, Hossein Jazani, Bijan’s father, a former officer in the gendarmerie, went to visit his friend, the principle of a high school. While there, he began to criticize and complain that his son who had already been in prison for 3 years, was dogmatic and that he was lucky to have gone to prison as opposed to a death sentence. We know this because someone close to him was informing on him to Iran’s secret security apparatus. This person was so close in fact that the authorities who received the information discussed below were worried that trying to verify it would blow this person’s cover.

Bijan and his father by all accounts had a contentious relationship. His father, had been a member of Iran’s communist party and then an active member of the Pan Turkish, pro-Soviet, Azeri rights party, Ferqeh-yi Demokrat-e. Azarbaijan. He escaped Iran in the 1945 and took refuge in the Soviet Union, where he married a Russian woman. Problem was he already had a wife, Alamtaj Kalantary and children in Iran, Bijan being one of them. Twenty years later, Hossein returned to Iran after being pardoned by the Shah.

When kvetching to his friend about his imprisoned son, Hossein lamented that when he had returned to Iran, his son told him that he’s sold himself to the ruling system and “hurled many accusations at me.” Until one day they argued with each other for “close to 3-4 hours.” Hossein recalled “I told Bijan in these conditions [where the might of the monarchy can crush the opposition] , you want to be the creator/موجد of a revolution? Don’t play around with your life and the lives of others.” But Bijan was having none of that: “You’ve sold yourself and have betrayed the revolution and the masses of Iran. You’re not qualified to advise me.” Hossein kept pushing back, trying to reach his son through paternal emotions: “We can be divided in our thinking but biologically, no matter what, I’m your father and we can instinctively protect our father-child relationship. Then I mentioned the book The Gadfly to him and summarized the contents for him. Eventually, Bijan and I remained estranged until he was arrested and given a 15 year sentence.”

On April 18, 1975, Bijan Jazani and 8 other political prisoners were secretly executed. At the time, the press reported that they had been shot outside Evin prison while trying to escape. No visual documentation of their execution exists but decades later, the Iranian artist Azadeh Akhlaghi carefully imagined and constructed their execution scene as part of a larger photographic project titled “By an Eyewitness.”

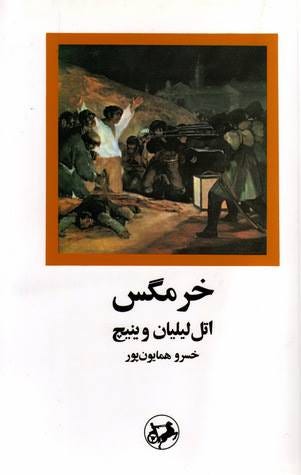

I have looked at these remarkable photographs a lot. But it was not until recently that I realized how Akhlaghi’s depiction of Jazani’s execution (above) borrows from Francisco Goya’s “The Third of May 1808” a painting that commemorates Spain’s resistance to Napoleon’s invasion. Goya also depicts a firing squad in the midst of killing some men but his painting includes bystanders who are bowing their heads or holding their faces in their hands, unable to witness the carnage in front of them. Several bodies are already shot, their blood staining the earth red. A man wearing white, the only figure not in earthen or dark colors, is on his knees with his hands up in the air staring down the barrel of the bayonets about to end his life.

Goya’s painting, this exact painting, has been the cover of the Persian translation of The Gadfly since it was first published. It would have been what Bijan Jazani’s father held in his hands when he read the book that he told his son about the last time he saw him free.