The Handwriting is Not on the Wall

On the Islamic Republic of Iran's head scratching "supplemental punishments"

One of the most annoying and yet, in the light of nostalgia, endearing homeworks we had to do as kids in Iran was “roonevisi” or hand copying an already printed text. Homework in Persian is مشق شب [mashq-e shab], literally night exercises. The reasons kids were made to spend their evenings copying things by hand into a notebook was at times to improve our handwriting, at times to help memorize something or another, and at time just to punish us (or so it felt) with just busy work. The educational system in many ways was based on rote learning and what better way to learn than by spending hours just copying something and getting cramps in your hand from holding a pen. (If you read Persian, you can take a look at the debates raging in Iran in 2018 about whether roonevisi should be eliminated from nightly homework here.)

The endearing part is remembering what it felt like to open up a new notebook (a universally delightful thing to do), take a ruler, take a number of colored pens (usually the ubiquitous Bic pen), and get to work. That first page held the always-broken promise that this time, it would not be painful.

It should have been painful to watch the video released by the photojournalist Yalda Moaiery in early January, 2023 announcing her sentences for “crimes against state security” (and its variations thereof) after serving about 3 months in prison. But the combination of the bright orange uniform of municipal sweepers that she had donned, her hair tucked under a hat, and her sardonically defiant tone dares you to feel anything but admiration. (Watch the video if you haven’t already.) Her sentence is 6 years in prison, but, she notes, she also got what is called مجازات تکمیلی or literally supplemental punishments: She cannot live in Tehran and neighboring areas for 2 years, cannot leave the country for 2 years, cannot use a cell phone or social media for 2 years, has to write a 100 page research paper on Morteza Motahhari, an activist cleric close to Khomeini who was assassinated less than 3 months after the 1979 revolution, and for two months, she must work as a park sweeper. Where’s the humiliation in that, she proudly asks, as she holds a broom.

Supplemental punishments are meted out at the discretion of the judge based on whether he believes the punishment that the law has ascribed to the crime is sufficient. When he believes that they are not (as in the case of Moaiery), he can add a whole series of other things to the sentence, though the types of things that can be added must abide by article 23 of the Islamic Republic’s penal law and cannot be longer than two years. These include things such as a ban from leaving the country, “confiscation of the means by which the crime was committed” (thus the cell phone ban for example), undertaking public works (sweeping the park), and obligatory education or learning a new job. While on paper the nature of the supplemental punishments are meant to be restorative justice عدالت ترمیمی, the recent spate of supplemental punishments issued in connection with the 2022 protests in Iran has drawn attention to the arbitrariness and the petty vindictiveness of the judges assigning these punishments (see Shargh newspaper’s excellent discussion of this.) For example, one of the supplemental punishments assigned to the activist Hossein Hashemi, who was sentenced to 6 years in prison after the November 2019 protests (known as Bloody Aban for the Persian month it occured in), was to work for a month as a “corpse washer” in Tehran’s main cemetery, Behesht Zahra, for four hours a day.

Not all sentences include these “public works” but almost all of the supplemental punishments given for what the state deems as “political crimes” seem to include either research projects and/or hand copying books. As noted above, Yalda Moaiery, was sentenced to writing a 100 page research paper on Morteza Motahhari, a punishment his outspoken son and former member of parliament, Ali Motahhari objected to. In a letter to the head of Iran’s judiciary, Motahhari noted that by making familiarity with his dad’s works part of someone’s punishment, they are merely creating a negative connotation in society’s minds about his scholarship. He asked that this part of the punishment be lifted.

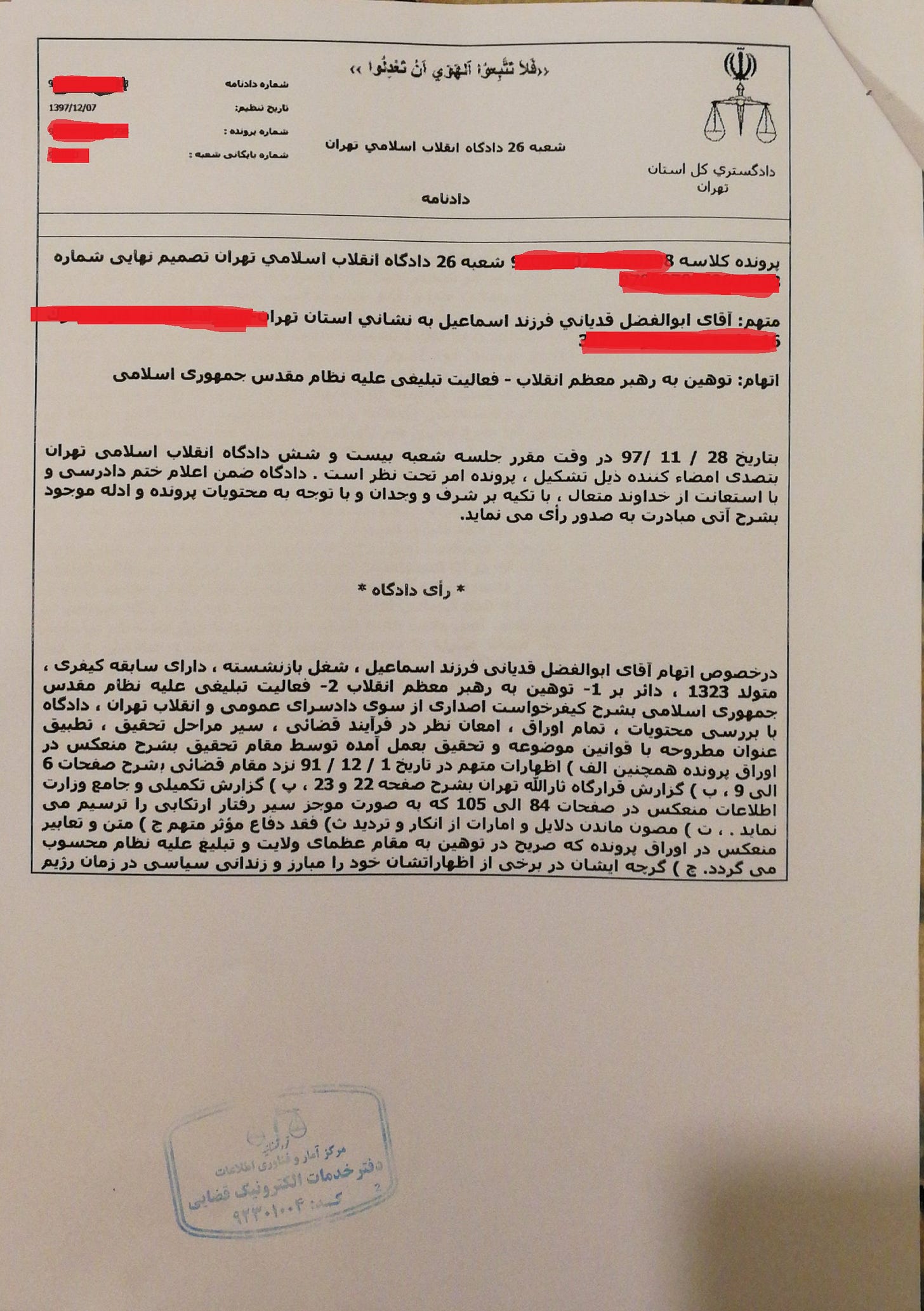

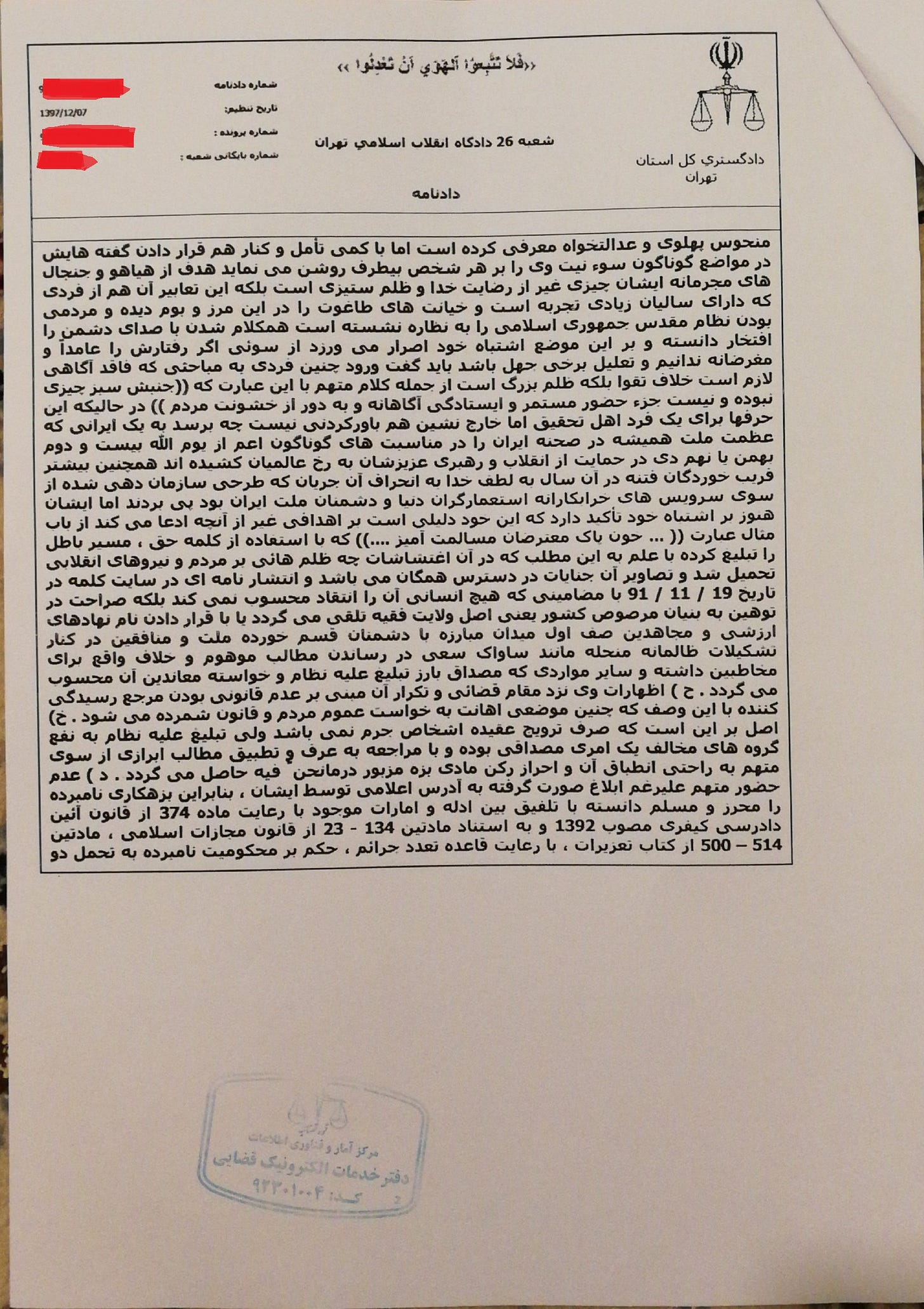

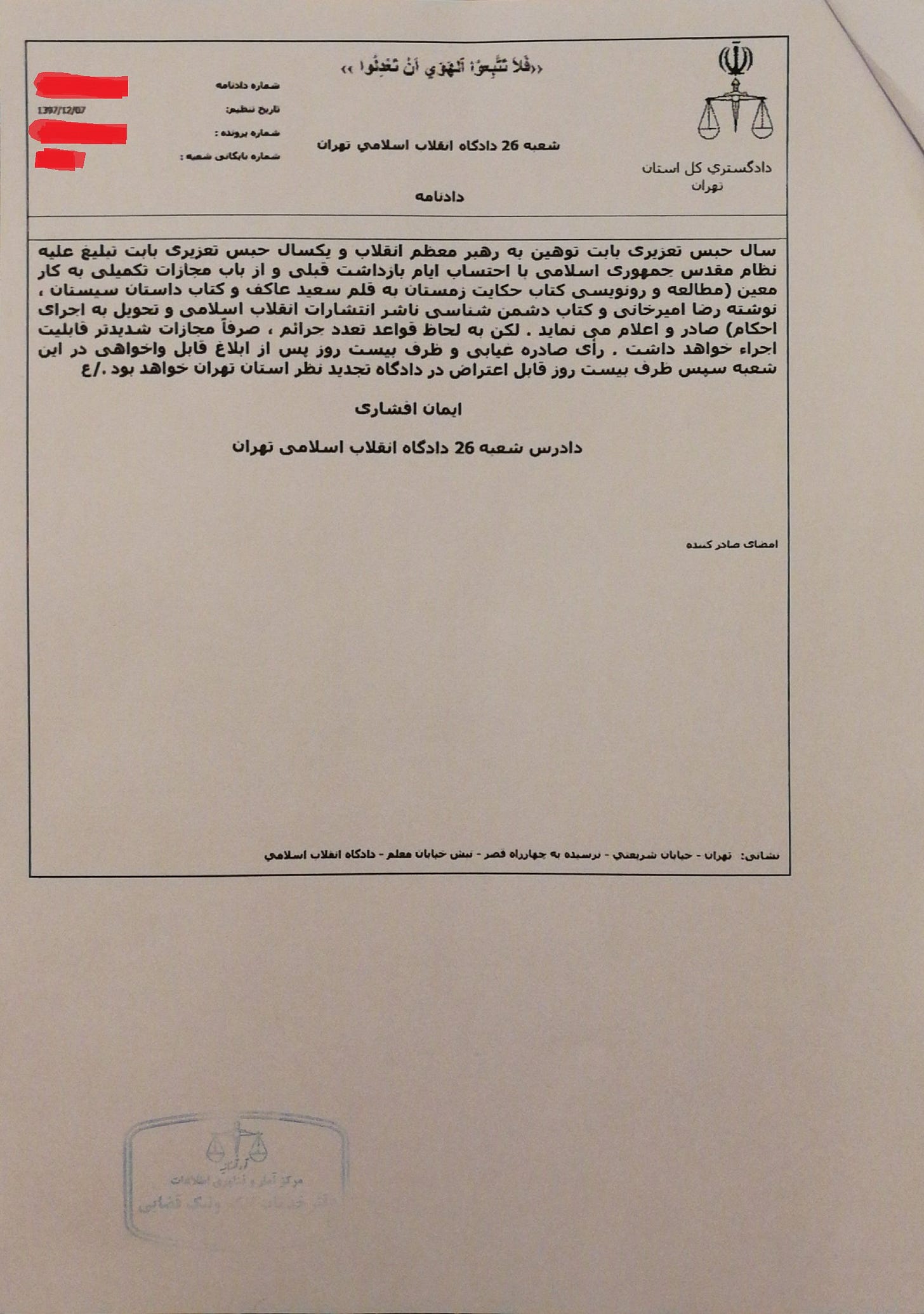

This was not the first time a government insider objected to a judge using someone’s writings as a punishment for a political crime. In March 2019, Abolfazl Qadyani (a former revolutionary turned critic) was sentenced to 3 years prison and “the study and hand copying” of 3 books either about or by Iran’s supreme leader, Ali Khamenei. Below are photos of his official sentence posted by Qadyani’s son on social media to also give you a sense of what these documents look like:

In Qadyani’s case, the office responsible for “the preservation and distribution” of Khamenei’s writing objected to this supplemental punishment noting that the use of the supreme leaders’ writings as a form of punishment is “in bad taste.”

I’m sure being the quick-eyed readers that you are, by now you’ve noticed that copying texts by hand is a supplemental punishment that’s being doled out. In Hossein Hashemi’s case, in addition to being a corpse washer, he was sentenced to handcopying “Three Minutes on Judgement Day” (a “novel” about someone who died for 3 minutes and other stories of experiencing the afterlife) and “53 Years of the Pahlavi Dynasty According to the Royal Court,” a book I tried and failed to read due to the boredom that set in every time I looked at it. According to one report, once he was done, the court would compare it to his handwriting to make sure he had done it himself and ask him 10 questions about what he had copied to determine his mastery of the materials.

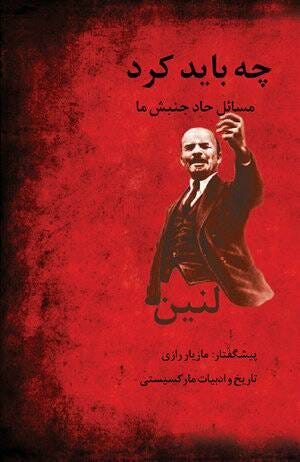

It’s clear that roonevisi of texts as a supplemental punishment has a similar logic to handcopying texts as part of the educational system in Iran. But interestingly enough, there’s a third way in which this strangely out-of-time practice resonates in Iranian history: As a political act in the decades leading up to the 1979 revolution. As I’ve written elsewhere a large number of people I have interviewed for my book on the revolution “defined their early political activity as copying illegal books manually in order to distribute them.” Their reasons for this painstaking act was based on the sensitivities of the Pahlavi state towards particular types of books, and the forms of repression around that. Some books (Lenin’s What is to be Done? keeps popping up) were so illegal in Pahlavi Iran that just having it or reading it could land you in prison, let alone printing and distributing it. So what was to be done? Use carbon copy paper to make multiple copies for later distribution, that’s what.

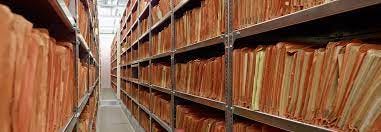

For a system as opaque as the current regime in Iran, these supplemental punishments provide a fascinating insight into its judicial system beyond the brutal repression felt everyday by its citizens. Roonevisi in particular, be it as punishment, education, or political opposition, binds Iran’s revolutionary past to the the fire burning under the ashes in its present. The notebooks in which the kids write their nightly roonevisi are thrown out year after year. The hand copied books by students and young activists in the 60s and 70s are most likely gone for all intents and purposes. But the supplemental punishments in the form of research papers and hand copied texts will/are probably logged and then archived in the bowels of the paper-loving bureaucratic state that is the Islamic Republic of Iran.

When the Stasi was dissolved in 1990 shortly before German reunification, the availability of its archives to the everyday person became synonymous with the end of a regime that had meticulously spied on its citizens. This link between the opening of a repressive regime’s archives and the promise of freedom after the fall of said political system is not unique to Germany (though it has left indelible marks on our popular psyche). The historian Kristen Weld tells the story of the Guatemalan secret police archives in Paper Cadavers and in My Life as a Spy, the anthropologist Katherine Verdery gets access to the file the secret police kept on her during her fieldwork in Romania in the 1970s: “There's nothing like reading your secret police file to make you wonder who you really are."

I think about this often. Not only because I’m an historian and the powers-that-be will kick you out of the profession if you don’t think about archives once a day (I jest?) but because I hope within my lifetime I can see an Iran in which young men don’t get executed in the darkness before dawn for taking to the streets in protest, journalists like Niloofar Hamedi and Elaheh Mohammadi don’t languish in prison for doing their job so bravely, photographers like Yalda Moaiery aren’t exiled from their homes and banned from doing what they love and doing it so beautifully, and people like my friend Siamak Namazi don’t spend years and years of the most important times in their lives in prison held hostage for who knows what. I know when I see that day, it’ll also be a day that the doors to the archives are flung open. When they do, I’m going to make a beeline for all the handwritten texts it holds inside, all these texts that stand for the promise no longer broken that the future will be better than the past has been so far.

This totally reminded me of reading handwritten copy of تاریخ حزب بلشویک on the staircase of the Mechanical Engineering building at Tehran Polytechnic in late 1970s. Starting from the 5th floor reading page-by-page, literally step-by-step, down to the exit door. Thank you for writing. I am going to do a longhand version of this and post it on my webpage, not as a punishment, just for fun.