There is a Crack, a Crack in Everything

Today at dawn, I said to a loved one: I think this morning I want to write about this practice of the Islamic Republic in Iran of not giving the bodies of the people they kill back to the families and instead just burying the body and then informing the family. I have been thinking a lot about that. About when the body is given, when it isn’t, and what fundamental elements of knowing and mourning they take away from grieving families, why it’s happening, and what happens when like the case of Mahsa Amini there is a burial and a funeral that sparks further grief and rage in people. There is so much to this issue: Lessons a revolutionary government has taken from its own past of using funerals as political platforms, how they didn’t mark or marked through desecration the graves of the political prisoners killed during the power struggle in the early years of the post-revolutionary days, and of course Khavaran.

But my loved one said it’s the holidays, write about something with more hope in it. And so I thought and I thought, and it was hard to come up with anything، particularly in light of the news that the Taliban have now banned women from university education. So I said: Like what? And she said, like this photo from Tehran’s metro from a week ago:

So for today’s post, let’s try to find the sliver of light coming through the cracks:

For the past couple of days, Tehran was covered in this yellow smog and as a result schools in Tehran and several other cities went online and day care centers were closed. There was a warning for the very young and the very old to stay indoors.

The rumor though going around among some people is that the government purposefully upped the burning of furnace fuel (mazout in Persian via French) in order to shut down schools as a way of gaining control over protesting students. This morning it rained a bit in Tehran.

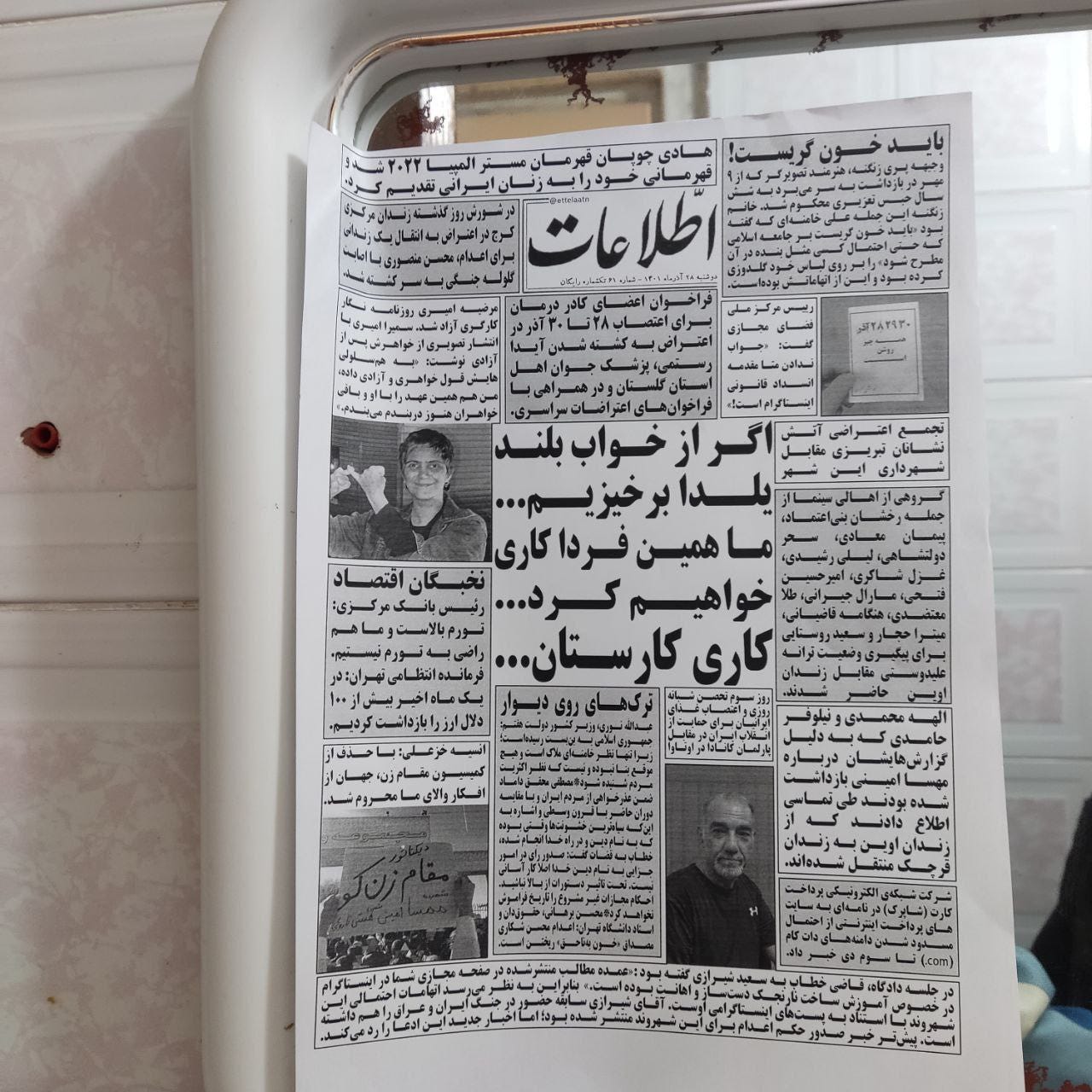

The various telegram channels and social media spaces that for the past 3 months were brimming with insanely courageous protests by university students in particular has now been taken over by lists and lists and endless streams of name of students being arrested. The sliver of hope in this is that it also contains the names of students being released almost always on some kind of bail. So the usual rhythm of arrests and release by the IRI continues. But then once in a while there is also creative forms of continuing some kind of political protest despite the unforgiving repression. My favorite for today is this old school (old school i.e. paper!) form of distribution of news by the university students in a northern city of Iran. The bulletin/pamphlet/samizdat is one page printed with the font and layout of one of the oldest government newspapers in Iran, Ettelaat.

This appropriation of the government’s newspaper for students to spread their own news includes news of the journalist Marzieh Amiri’s release from prison, the transfer of Nilufar Hamedi and Alaheh Mohammadi (the two journalists who covered Mahsa Amini’s death early on in September and have been imprisoned since) from Evin prison to Qarchak prison, and that the former interior minister under Khatami who himself has spent time in prison said the Islamic Republic of Iran has reached a dead end. This last item appears under the title: Cracks on the Wall.

َYesterday one of Iran’s newspapers, Etemaad (I know, it looks Ettelaat in English but it’s not that!) reported that the death sentence issued by the government for Hamid Ghareh Hassanlou, a radiologist arrested and accused of killing a Basiji in Karaj, has been withdrawn due to behind the scenes work by “a long standing distinguished official.” Hours later, the judiciary denied this news and said a final verdict has not been determined.

Lastly, today is the winter solstice, the longest night of the year called Yalda in Persian. As a child growing up in Iran, Yalda was always something acknowledged, i.e. we knew it was Yalda. I also remember my mom putting aside pomegranates in the fall, which by December were out of season, and carefully drying them so that by Yalda they could be cracked open and the inside would remain full of lovely red juicy seeds. But that was the extent to which Yalda was a thing for our family. Nowadays people wish each other happy/merry Yalda and write about its tradition and meaning and all that good stuff. I’m not a grinch and know that traditions are all invented even if their invented past does not necessarily align with everyone’s memory or experience. But as the wise woman who is my mother used to say: Every occasion to be merry is a good occasion so with that, let’s acknowledge the longest night of the year, anticipate the shortening of nights ahead of us, and revel in the amazingness that is pomegranates.