"You OK?"

Some thoughts on friendship, death, and headless chickens two weeks after the Iran-Israel ceasefire.

At a dinner party someone asked me did any Iranian civilians die during the 12-day war between Iran and Israel? “Over 700 people,” I said not noticing that the question had not been asked in good faith. “No,” they said shaking their head decisively “there were no civilian casualties in Iran. I don't believe that.”

Ironically, perhaps, growing up in the Islamic Republic of Iran in the 1980s has served me well in these days of disinformation. Or more accurately in these days in which the veracity of information is determined by the certitude of the person conveying it and the force of their wishful thinking. It rarely fazes me. I asked them to consider for a moment the density of a city like Tehran and consider for a moment the power of the bombs and missiles that fell on it. “Even if you hit your target, let's say the 4th floor of a nine-story building,” I said calmly, “the laws of physics dictate that damage would also be done to the other floors. On those other floors there are children, there are families, there are somebody's loved ones who did and could die. There’s the force of the blast, there’s debris, there are so many ways that civilians could be injured or killed.”1

My dinner companion blinked. A pause. “No,” they said. “I have a hard time believing that.” Then they turned and took a bite of their dinner.

When the war with Israel started, my oldest and closest friend, Rahaa, had been my focus of worry and my source of news. I started joking that she was the Rahaa News Network. It’s not that I don’t have family in Iran. I have a lot. But I could get their news from my mother’s efficient reporting: “Just now I Facetime and everyone is safe,” she would text. When on the 4th day of constant strikes on the city that holds her remaining sister and brother she wrote: “I don’t know what I can do to help,” all I could say was “You can’t do anything. It’s just horrible.” I hoped the simplicity of my words would mask how her messages were breaking my heart.

Rahaa and I met in the 4th grade. I was the odd American kid who sat in the front row on the left side of the classroom, often head in an English book. She sat in the back row on the right side, often staring at my shoes, which she now tells me she coveted. We became friends when I invited her to join the group I had formed with two other 4th graders. We went to a room all the kids believed was haunted (a cobwebbed storage room in the back of the school full of dilapidated desks) and signed an oath to always be friends and to take down the rival gang in the other fourth grade homeroom. I wanted the oath to be signed in blood. Rahaa, ever the cautious and sane one, suggested we use a red pen.

On days when we all had some pocket money, the 4 of us would walk up the sycamore lined Vali Asr boulevard and go to the juice store to buy one sweet “piroshki” and one sour zereshk juice (made from pureeing soaked barberries.) Then we’d walk a bit up and down from our school, talking until the treats had vanished. I would take tiny sips and minuscule bites, wanting the sweet and sour tastes and time with my friends to last forever before getting on the bus to go home.

I’ve written elsewhere about how Rahaa was my entry into the revolution.2 She had already seen a revolution come and stay. I had missed it, biking in the leafy streets of San Diego.

By the time we were 16, we had both seen a war come and stay and then go. We lived in the same neighborhood. We went to school together and gave nicknames to all the boys who took the city bus with us every morning. We took forever and a day coming back home from school, often ducking in and out of the bookshop lined street in front of Tehran University. We would laugh so hard, we would pee our pants, and then double down in laughter in the street from having done that. When my family immigrated to the US, we wrote our names and the date in blue crayon on the wall behind my bedroom door. I gave her my yellow teddy bear I had owned since I was 7, a cuddly sinister creature with just one plastic eye. She tells me she still has it.

The first night this June when drones swarmed over Tehran, knowing that Rahaa lived alone, I’d texted her “you ok? You’re alone?” I’m ok, don’t worry, she wrote back. The next day I texted her the same because honestly, all questions at the time seemed so dumb. “You ok?” just slightly less so. “I’m ok. I was vacuuming and took a break and sat down when they struck.”

Same question the next day. “Last night you really felt like a space alien was coming through the windows. The drones seemed so close. I was too scared to go in front of the window,” she wrote me. And so on. And so forth. I was most freaked out when she went to the Caspian shore for 4 days to give her nerves a break from the non-stop bombs and I didn’t hear from her. I texted her “Hi! You ok?” I texted her every day. I texted her sister. But there was a nationwide internet shut down to combat the immense security breach the government had experienced. And her phone was not answering. I acted like a chicken with her head cut off, flitting from here to there, trying to contain my anxiety.

During those days a vast community of Iranians outside tried and tried to reach their loved ones. My mother texted me: “Two days. I can’t reach my sister.” My friends with elderly parents in Iran had permanent lumps in their throats, tears in their eyes, barely able to sit or sleep. Everyone’s “you ok?” went unanswered. My grad student reached out and said he has a way to reach people on the inside if there was someone I needed to contact. I hesitated. Rahaa? But I gave him my cousin’s number. Five minutes later my mom texted that she received a voice message saying my aunt and cousin were safe. “Thanks again,” she texted.

Recently, I found a series of articles I had written in Persian when I was 17 about my memories of the war of the cities when Iran and Iraq traded missiles over Tehran and Baghdad. When I wrote those, it had barely been a year since the last bomb had fallen in Tehran. The writing is maudlin. The feelings so raw, I want to hide from them under the table. On the first night of the missile attack in March 1988, after the last (and seventh) missile fell, I wrote that “I was running around the house like a chicken with her head cut off.” Apparently, the body does remember. In my case how to be headless poultry under stress.

It’s been exactly 2 weeks and a day since the ceasefire went into effect and things in Iran are going back to…I’ll say normal but that’s just not the word. Shops are open, people are back at work. Kids in school. Air pollution is off the charts.

Those of us outside of Iran have stopped texting those inside every 30 minutes saying: “You ok?” I’m no longer waking up every morning expecting to find out that someone I love is buried under rubble. (I lie…Every morning I still wake up and hesitate to look at my phone. I always expect death to come knocking on its screen.)

I’m finding myself in a strange place. Things seem like before but at a slight tilt. I’ll be talking about something banal, like a book I just read, and catch a tiny wave cresting in my throat about to travel up and break out of my eyes. I’m sentimental sure, but a cry baby I am not. But war does that to you even when you’re 3000 miles away.

After the dinner party, I said out loud something I had kept in my head all this time. I confessed to my husband that I had been thinking every day of the war, and every day since, how weird it was that no one in my life died either during the Iran-Iraq war and now this one. I didn’t want to think this, let alone say it, for fear that I would be punished. That someone I loved would die under the rubble of a building or from the blast of a bomb or from shards of glass shattering in every direction.

“I know the odds are not high,” I said closing my eyes. “But every bomb makes it feel like it’s your turn now.”

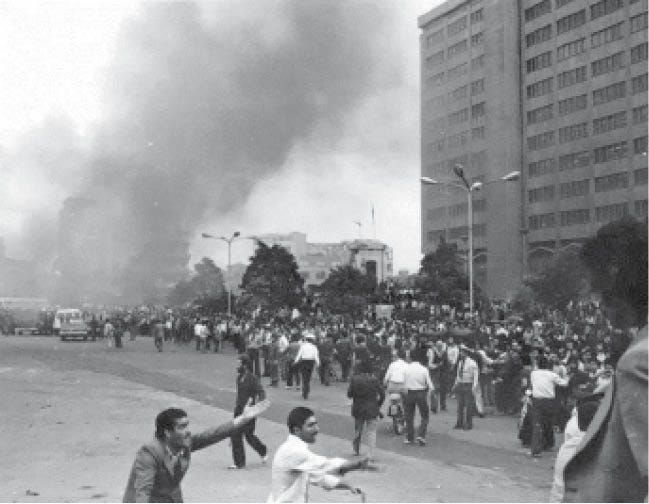

The photo was posted by Elahe Mohammadi on her X account as part of a fascinating reportage she has done on 6 photographers in Iran who worked against state censorship and other obstacles to document the war. You can see the other photos on her account and read her article here. Ms. Mohammadi was arrested and imprisoned in September 2022 for reporting on Mahsa Amini’s funeral. She and her colleague Niloofar Hamedi were finally released in January 2024 and eventually pardoned.

“Someone’s Daughter” https://www.americanacademy.de/someones-daughter/